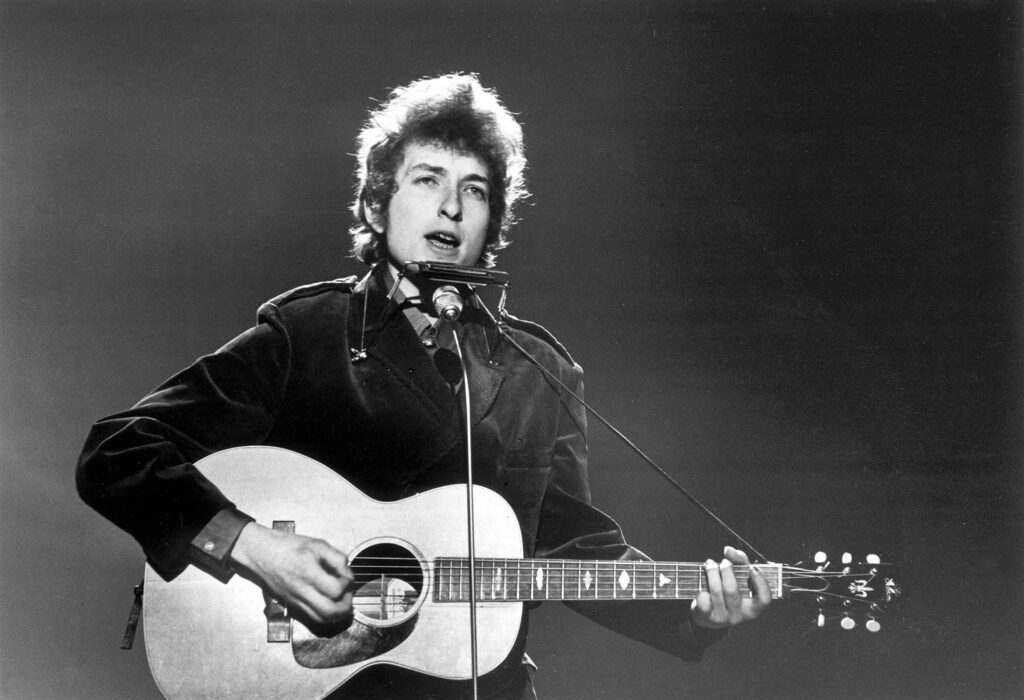

Het blijft niet onopgemerkt. Op maandag 24 mei viert Bob Dylan zijn tachtigste verjaardag. Zijn betekenis voor de popmuziek is onomstreden, maar zijn lange carrière stond altijd in het teken van controverses. In aanloop naar de verjaardag van het fenomeen deelt Heaven-redacteur Ludo Diels vier bespiegelingen. De eerste: over de Nobelprijs en cultureel onbegrip.

Go to the bottom of the page for the English version

Ik hield van Bob Dylan omdat dit nu eenmaal cultureel correct is. De muziek kon me diep in mijn hart maar matig bekoren, zijn stem vond ik ronduit lelijk en van die teksten waar men zo hoog over opgaf wist ik geen chocolade te maken. Ik was zeventien. Smaak is complex en niet vrij van elitarisme. Want wie in bepaalde popkringen geen modderfiguur wil slaan, moet Bob Dylan goed vinden. Meedoen om niet buiten de boot te vallen. Zo is de meeloper geboren. En menig Dylanfan, daar ben ik zeker van. Want Bob Dylan is beslist geen lichte kost voor de gemiddelde popmaag.

Dylan goed vinden gaat niet vanzelf, zo ondervond ik. Het is als het leren waarderen van spruit, bloemkool of tuinboon voor een kind. Van Dylan leren houden vergt tijd en soms geduldige mentoren. Meer nurture dan nature, eerder aangeleerd dan aangeboren, die (voor)liefde voor Dylan. Maar wie zijn muziek eenmaal goed vindt, blijft er, net als aan spruitjes, levenslang aan verslingerd. Ik kan erover meepraten. Bob Dylan is ontegenzeglijk de grootste.

Het is vaker gezegd: Elvis gaf de popmuziek een lichaam, Bob Dylan schonk haar de geest. Dylan markeerde, net als Elvis, een paradigmabreuk. Er is een tijd voor hem en een periode vanaf zijn eerste album. En dan zijn er nog tal van breuken bínnen zijn zestig jaar omspannende carrière. De ene keer gaat hij elektrisch of is hij in de Here om dan ineens via country een bigband koers te kiezen en daarna weer terug te keren naar blues en rock. Geen peil op te trekken. Onnavolgbaar. Dylan is, vergeef me het cliché, een eenmansuniversum.

Geen wonder dus dat men een studie kan maken van Bob Dylan. Niet met de hoes losjes in de hand, maar serieus met de neus in archieven doet men aan bronnenonderzoek: dylanologie. Voer voor vorsers. Sommige geleerden noemen his Bobness in dezelfde adem als Ovidius, Vergilius en Dante. Bob Dylan is geen voer voor lichtgewichten.

In zijn teksten vliegen de bijbelse allusies en klassieke referenties je om de oren – althans dat beweren de liefhebbers, schriftgeleerden en dylanologen.

Volgens zijn Nobelprijsspeech uit 2017 vormden Moby Dick, Im Westen nichts Neues en de Odyssee het fundament onder zijn artistieke bestaan. Niet alleen zijn teksten ademen literatuur, zijn artiestennaam is een verwijzing naar dichter Dylan Thomas. Overigens had hij meer affiniteit met poëten als William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, T.S. Eliot en de Beat Poets Allen Ginsberg en William S Burroughs dan met Dylan Thomas, over wie hij ooit tegen een journalist in 1966 schijnt te hebben gezegd: ‘I did more for Dylan Thomas than he ever did to me.’ Hij bleek niet zo geporteerd van de masculiene romantiek die uit de gedichten van Thomas sprak, zo verklaarde hij. Feit is dat Bob Dylan altijd omgeven is door een Hauch van literatuur. Dylan is in veler perceptie dus meer dichtbundel dan songbook.

Bob Dylan is niet geïnteresseerd in what it all means. Liedjes moeten klinken, daar gaat het om. Liedjes, net als de werken van Shakespeare, waren bedoeld voor het podium en niet om te worden gelezen. Die Nobelprijs voor de literatuur had hij dus eigenlijk niet verdiend. Dylan is geen dichter. Die Nobelprijs had hij moeten krijgen als componist, als zanger. Maar kennelijk staat de zanger lager in de rangorde dan de dichter. Om een popliedje meer te laten zijn dan het is, bestaat al sinds jaar en dag de neiging om het de wereldliteratuur in te slepen. Popmuziek heeft de grote kunst nodig om relevant te zijn. De rechtvaardiging van popmuziek – en dus ook van Dylans oeuvre – is gelegen in de behoefte om haar afkomst te verloochenen. Wat in wezen platvloers is – cultuur voor cultuurlozen, zoals de gevierde popjournalist Dave Marsh ooit stelde – moet zo nodig worden opgetild.

De waarde van popmuziek wordt echter schromelijk miskend. Het is kunst met de kleine letter, inferieur en ondergeschikt aan de hoge kunsten. Popmuziek wordt als onvolwassen gezien, ze heeft vaderlijke steun nodig – goede voorbeelden. Als Bob Dylan in zijn ruim zestig jaar omspannende loopbaan iets heeft aangetoond dan wel het grote ongelijk van die cultureel correcte aanname dat er een hiërarchie in de kunsten bestaat. Woody Guthrie was even effectief en bezat net zo veel zeggingskracht als John Steinbeck. Het zijn andere wegen naar hetzelfde hart.

Popmuziek kan op haar eigen benen staan. Ze heeft geen grote literatuur nodig om zich te bewijzen. Popmuziek bewijst haar nut elke dag door mensen daar te raken waar het ertoe doet. Dylans muziek doet precies dát. Het raakt je in de kern. Daarin schuilt de betekenis. De ironie is dat houden van Dylan inmiddels zelf cultureel correct is. En wie een ander niet kan overtuigen dat zijn liedjes grote kunst zijn, vanwege de sterke melodieën en composities, die kan altijd nog de Nobelprijs van stal halen. Wie die prijs ontvangt, die is boven elke culturele twijfel verheven. Hoe erg is dat!

Dit artikel is gepubliceerd op Heaven magazine

Culturally correct appreciation, or honest appreciation?

Honest appreciation.

I loved Bob Dylan because it was the culturally correct thing to do. Deep in my heart, the music didn’t do much for me. I thought his voice was just ugly and I could make no sense at all of all the lyrics people held in such high esteem. I was seventeen. Taste is complex and it is not free of elitism, because you have to like Bob Dylan in certain circles in the pop music industry if you don’t want to look like a fool. You have to join in to make sure you aren’t left out. This is how the follower was born. I am sure this applies to many other Dylan fans. After all, Bob Dylan is no light fare for the average fan of pop music.

Liking Dylan isn’t something that happens naturally, in my experience. It is like a child learning to like Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, or broad beans. Learning to like Dylan takes time and, sometimes, patient mentors. It’s more nurture than nature, the preference for or love of Dylan. But – much in the same way as Brussels sprouts – once someone starts liking his music, they will continue to love it till the end of their days. I can tell you that from first-hand experience. Bob Dylan is, without a doubt, the greatest.

It has been said before: Elvis gave pop music a body; Bob Dylan gave it a mind. Much like Elvis, Bob Dylan marked a paradigm shift. There is a time before him, and a time after his first album. Furthermore, there are many other shifts within his sixty-year spanning career. At one point he opted to be backed by an electric band, at another he was born again and chose to go in the big band direction via country music after which he returned to blues and rock. There’s no logic to it. It’s inimitable. Dylan is, forgive me for the cliché, a one-man universe.

It’s no wonder that people can create a study program out of Bob Dylan’s career. Not with a light grip on an album case, but by taking a serious dive into archives and researching sources: dylanology. It’s perfect for true researchers. A number of scholars mention his Bobness in the same breath as Ovid, Vergil, and Dante. Bob Dylan is not for the faint of heart.

His lyrics are packed with Biblical allusions and references to classics – at least that’s what fans, scholars, and dylanologists all say.

In his 2017 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he said that Moby Dick, Im Westen nichts Neues, and the Odyssey formed the foundations of his artistic existence. His lyrics radiate literature and his stage name is a reference to the poet Dylan Thomas. Furthermore, he felt more affinity towards poets such as William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, T.S. Eliot and the Beat Poets such as Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs as opposed to Dylan Thomas. On this topic he apparently said the following to a journalist in 1966: ‘I did more for Dylan Thomas than he ever did to me.’ He explained that he was not too impressed by the masculine romance expressed in Thomas’ poetry. The fact is that Bob Dylan has always been surrounded by a Hauch (breath) of literature. Many people perceive Dylan more as a collection of poetry as opposed to a songbook.

Bob Dylan is not interested in what it all means. Songs need to sound good, that’s what it’s about. Songs, like the works of Shakespeare, were meant for the stage and not for reading. In other words, he had not really earned the Nobel Prize for literature. Dylan is not a poet. He should have received the Nobel Prize as a composer, as a singer. However, apparently the singer is lower in the pecking order than the poet. To have a pop song represent more than what it is, people have long tended to incorporate literature from around the world into said pop songs. Pop music needs high art to be relevant. The justification of pop music – and therefore of Dylan’s body of work – lies in the need to reject pop music’s roots. In essence, what is banal – culture for the cultureless as once posited by the celebrated pop journalist Dave Marsh – seems to need to be elevated.

However, the value of pop music is grossly misjudged. It is characterized as art in lowercase, inferior and subordinate to high art. Pop music is seen as immature and in need of paternal support – good examples. If Bob Dylan’s 60-year spanning career has demonstrated anything, then it has shown the large disparity of the culturally correct assumption that there is a hierarchy in the arts. Woody Guthrie was equally effective and had the same power of expression that John Steinbeck did. These represent different roads to the same heart.

Pop music can stand on its own two feet. It does not need great literature to prove itself. Pop music proves its work every day by touching the lives of people where it matters. Dylan’s music does exactly that. It affects you on a deep level. That is where the meaning lies. The irony is that the act of loving Dylan’s music has become culturally correct. And if someone cannot convince another person that Dylan’s songs are great art because of his powerful melodies and compositions, they can always bring up the Nobel Prize. Whoever receives one of those is exempt from any questioning of whether they are cultured or not. Isn’t that terrible?